PART 2: Entities and Value Objects

In the first part of this series of articles on Domain-Driven Design, I talked about the characteristics of an effective model, the construction of the ubiquitous language, and the essential value of maintaining a direct interaction between domain experts and developers, to have a modeling that really brings value to the business. If you haven’t read it, I suggest starting there:

Domain-driven design, from the beginning to code

With a team that has this mindset, and a dose of obsession with deeply understanding the domain (knowledge crunching), supported by an agile method, then we can implement DDD.

In this example, we are going to model a marketing automation system. I chose this domain because I have a domain expert who lives with me. 🙋

My wife has already worked with two marketing automation platforms, including Mautic, which is an open-source marketing automation system that is very popular in this market.

Furthermore, this domain seemed to be a good challenge to simulate the knowledge-crunching process and the formation of the ubiquitous language, since I didn’t know anything about it. 🤔

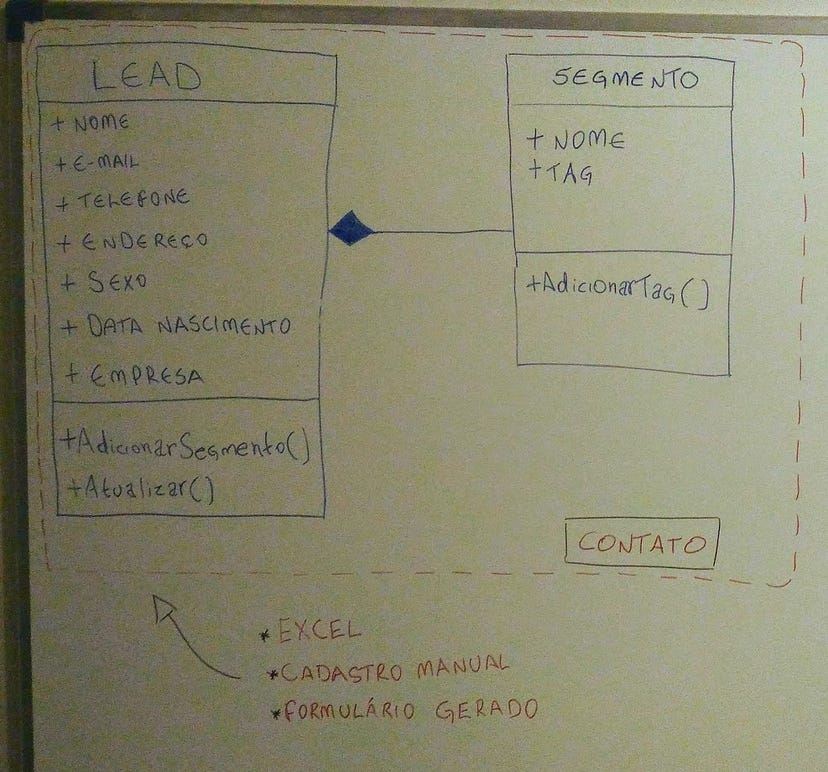

After several questions and some brainstorming, I was able to draw this initial model:

ME: What are marketing automation systems for / what is their function?

SHE: Serve to capture and centralize leads (possible customers) in one place.

ME: How are leads captured?

SHE: In 3 ways:

- By importing an existing customer base (excel).

- Through manual registration.

- Through a generated form, where you ask the visitor to inform, among other data, the e-mail. By doing so, this form will be sent to Mautic.

ME: I understood. And what is the lead data that is captured through these 3 ways?

SHE: It depends on the capture method.

ME: Right, but what is the minimum essential information for a lead to exist?

SHE: The minimum is the name and e-mail, which, indeed, are two valuable pieces of information for converting a customer (sale).

ME: And what are all the possible data that a lead can have?

SHE: [after thinking about it for a while…]: Name, email, segment(s), phone, address, gender, date of birth and company.

ME: [after reflecting on the data…] What are segments and what are they for?

SHE: Segments are ways of classifying leads that will later be used in campaigns.

ME: There’s a new term here: campaigns — what are they?

SHE: Campaigns are sequences of emails sent to leads. For example, I might have the campaign “e-Book Download: How to Accelerate Sales” or “Live Webinar Registration: Accelerate Your Startup”. When creating a campaign, I configure a sequence of emails with a scheduled date and time, and I can also put conditions in these emails…

Our dialogue continued like this for a long time, where I learned about the domain, and together we created the initial model.

But I will interrupt it so as not to go on any further. Also, with this part of the domain, we already have enough code to start implementing the DDD building blocks.

Entity

By definition, an entity is an object that has an identity, and that identity persists throughout the lifecycles of that object. Every developer knows what an entity is. But is everyone modeling entities correctly?

Analyzing the model, I identified the entities: Lead and Segments.

Below is the Lead entity code:

But look at the code above. What’s wrong with this entity? Well, several!

-

It does not inform the data it needs so that we can create a valid instance (it has the default constructor).

-

Reference types are not being initialized, so when accessing, them we will have an exception:

var lead = new Lead();

lead.Segments // We got a NullReferenceException here.

-

Does not have encapsulation! All properties are public, rather than having a well-defined, public interface to access them.

-

It’s all made up of primitive types, it has no intelligence and doesn’t make any reuse.

It is a typical anemic entity, without knowledge, and therefore without value to the model. The set of entities in this format, among other code smells, characterizes an anemic model, which is the opposite of what we want.

So we have these 4 problems. Let’s solve it one by one:

- Solving the first problem (defining a constructor that clearly shows us the what data we need):

Now Lead informs what it needs for an instance of it to be created (name and email).

- Now let’s solve the second problem (initializing Segments to avoid an exception):

- Solving the third problem (the lack of encapsulation):

Let’s review what we’re doing above.

We are protecting the data through encapsulation (note the private visibility modifier).

To protect Segments from being updated outside of our public interface, we need to use the IReadOnlyList interface.

If we use ICollection or IList, despite the property being private, it would be possible to access the Add() or Remove() method and add or remove items outside the public interface, thus breaking the encapsulation:

var lead = new Lead(…);

lead.Segments.Add(…);

lead.Segments.Remove(…);

The IReadOnlyList interface does not have the Add() and Remove() methods, therefore, an instance of Lead can only have its Segments updated through its public interface.

Note the role of encapsulation, not only providing data security but also adding knowledge to the domain.

We are hiding the complexity of data and internal operations from the Lead class client, and exposing only its public interface, which is what matters to him.

We did this via the CompleteInfo(...) method.

By the way, the name of the CompleteInfo(...) method, was taken from the language used by the marketer performing this operation — i.e. as soon as possible, he completes the Lead’s information with data he didn’t have when he got the Lead. Therefore, completing the information (Complete Info) is part of the ubiquitous language of this domain.

Even if for the developer, this is just an Update or Edit, DDD is about creating models that reflect the language of the domain, thus avoiding translations between developers and domain experts, and therefore, creating models that reflect the business through the code.

Note that now we make it clear how to complete the Lead’s information:

void CompleteInfo(string phoneNumber, string address, bool gender, DateTime birthDate);

Eric Evans calls these intention-revealing interfaces, that is, that make it clear to the client of the class how to use it.

He cautions that if the interface doesn’t tell the client what they need to know to use the object, they’ll have to dig deeper into the class’s implementation to understand it. Then the encapsulation value will be lost.

EVANS (2004)

By exposing only one public, well-defined interface, we simplify the use of the class by making it clear how a Lead should be instantiated and updated.

This way we avoid the overload of information that we are exposing to the mind of those who need to work with this class.

Otherwise, the developer would have to find out: “what 🤬 do I need to have a valid Lead, since there is no constructor that tells me this, and all properties are public?”

Remember: OOP is about decreasing complexity!

Now our entity is arguably much more in line with the model. However, there is still a problem to be solved, remember?

It’s all made up of primitive types, has no intelligence, and doesn’t do any reuse.

Look again at the latest version we have of the code. Notice that we are overusing primitive types:

string Name

string Email

string PhoneNumber

string Address

bool Gender

Except for Segments, we are using only primitive types (string and bool).

And this does not add any value to the model as it just represents a data structure. For example, how do I know if Email is valid?

What about PhoneNumber and Address, what is their format?

Relying only on primitive types, we can have a ridiculously valid Lead, like this:

var lead = new Lead(name: "", email: "(51) 9999-9999");

lead.CompleteInfo(phoneNumber: "Não lembro", address: "Que tipo de endereço?", false, null);

So let’s refactor the Lead class again, this time to replace the primitive types with Value Objects.

Value Object

Value Objects are objects that represent a descriptive aspect of the domain, but unlike entities they have no identity.

There are some extra benefits to using a Value Object:

Because they do not have identity, if implemented correctly, they can contribute to performance, since the same instance of a Value Object can be shared among several instances of an Entity. For example, all instances of Leads that live in the same place could share the same instance of Address.

For the same reason, Value Objects can implement functions free of side effects.

For our case, however, the initial interest in Value Objects is to add more richness to our model, and at the same time make it testable.

So let’s replace the primitive types (Name, Email, PhoneNumber, Address) by the respective Value Objects, according to the code below:

Don’t worry about the Guard.Against(…) methods, I’ll explain them later.

The Guard.Against(...) methods are Guard Clauses that serve to validate the Value Objects . Through the Guard Clauses, we create preconditions that must be satisfied so that we can advance to the next code statements. If these preconditions are not met, there will be an exception.

Therefore, if we try, for example, to initialize an Email with an invalid value, we will have an exception:

var email = new Email("foo@.com");

// FormatException: Invalid e-mail address: foo@.com.

In the next articles of this series, as our model evolves, I will demonstrate the use of the

CanExecute Patternand theNotification Pattern, which together allow us to offer the caller a way to test the operations before executing them, and in case of not being able to execute them — for violating the contract, returning the errors to the client.

The rules (which for now are just validations) are where they should be: in the domain. And they belong to their respective objects, which are no longer just worthless data structures.

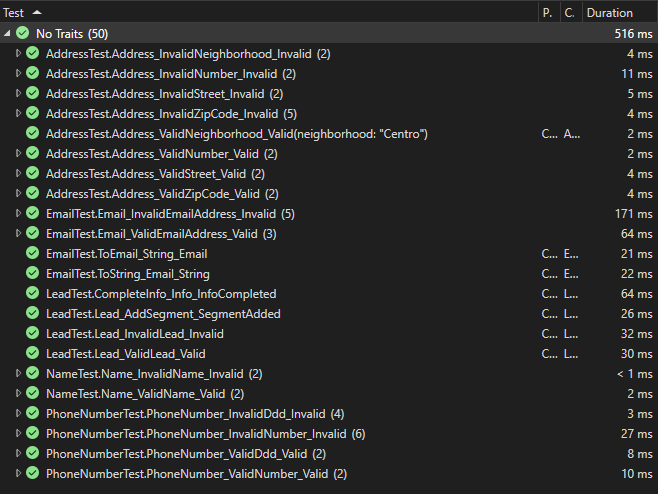

And speaking of rules, where there are rules, there are tests:

And to conclude, here is our Lead class refactored to contain the Value Objects and their respective tests:

If you compare the code of this version of Lead with the previous one, you will notice that, structurally, they are very similar. Basically, only the types have changed, which before were primitive and without value, and are now Value Objects, with well-defined validation rules and covered by 50 unit tests:

Surely, now instantiating and updating a Lead was a bit more laborious, after all, the Lead and Value Object constructors make explicit what they need to be instantiated:

On the other hand, now the cognitive effort has decreased considerably, as we no longer have to guess which properties are required in a new instance — never being sure, and each developer doing it in a different way, which in the end leads to a series of bugs — that is, it’s a very worthwhile tradeoff.

And if, in the future, there is a very complex constructor, we can mitigate this complexity through the Factory Method pattern.

Conclusion

There is a long way to go to implement DDD. But DDD will pay back several times that effort!

Where would these rules (which for now are just validations, later we will have the business rules) end up being placed if we were guided by the data-driven way of developing software, where we are guided by the ER model instead of the domain?

If we want to do object-oriented design, we need to temporarily forget about tables. Let’s remember them when we implement persistence. I repeat: when we implement persistence — And I’m going to show you how to map Entities and ValueObjects to tables, and even how to map Entities that have an inheritance relationship.

We’re creating object-oriented, extensively tested, and most importantly, code that reflects the language of the domain, and here we’re just scratching the surface — in the next few articles in this series we’ll model Aggregates with complex Entities, and then it’ll become more apparent the power that OO gives us in domain model design.

But to do that, first, I need you to understand 3 more essential building blocks of DDD: Domain, Subdomains and Bounded Contexts — and that’s what I teach in the next article.

References

- Evans, Eric. Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software. 2004.

- Vernon, Vaughn. Implementing Domain-Driven Design. 2013.