PART 3: Domain, Subdomains and Bounded Contexts

In the second part of this series of articles on Domain-Driven Design, we start modeling the domain of a marketing automation system. We created our first Entity and Value Objects, and saw 4 common mistakes in creating these, and how to solve them.

We create object-oriented code, extensively tested, and most importantly, that reflects the language of the domain.

In the end, I think it’s clear why it’s critical to forget about the ER model while we’re modeling the domain, and the consequence of not doing so.

If you haven’t read it, start there, because this article is a continuation of the previous one:

PART 2: Entities and Value Objects

I already talked about the difference between Domain and Domain Model here. If you don’t remember, reread this part now, because this should be clear for us to proceed with the understanding of the next items.

Today I’ll demonstrate two more fundamental building blocks of DDD: Subdomains and Bounded Contexts.

Subdomains

A point that often causes confusion, and consequently a big modeling error, is to think that the Domain Model should be a single model, which includes the entire Domain of the organization. But in fact, when we are using DDD, we do exactly the opposite, that is, we think about only one area of the business at a time.

VERNON (2013)

Thus, to organize and understand the Domain in which we are inserted, we must decompose it into Subdomains, which generally reflect the organizational structure of the business. For example, sales, inventory, shipping, accounting, etc.

We know that the Domain corresponds to the entire universe of the business, that is, the Domain is what an organization does, and the world in which it does it. On the other hand, when we want to refer to only one area of the business, we call it a Subdomain.

Core Domain

It is the most important Subdomain, it is the one that justifies the existence of the organization. For example, if the organization is a shoe factory, the most important area is the production and sale of shoes. This Subdomain that represents the heart of the business is called Core Domain. 💰

Generic Subdomains

In addition to the Core Domain, we know that there are other necessary areas that make an organization work. These areas serve to support the Core Domain in its function. In the case of our shoe factory, logistics are needed to distribute products, HR to hire trained employees, accounting to manage assets, among other areas. Within DDD, we call these areas Generic Subdomains.

Note that the Core Domain depends on the type of organization. If our organization were an HR company instead of a shoe factory, the Core Domain would possibly be R&S.

However, these are just examples. In real life, be careful not to make assumptions before you know the Domain well! If the shoe factory in our example has a super efficient delivery method, which gives it a competitive edge, certainly its delivery process is part of its Core Domain, as it is an important strategy for the business. 🎯

🤔 Was it just me or did you also think about Amazon now?

Bounded Contexts

Bounded Contexts is one of the hardest design patterns to understand in DDD, but it’s certainly one of the most important (more important than that is the Ubiquitous Language, and you’ll understand why).

That’s why we’re going to, step-by-step, explain what it is, where it is, and what it’s used for, in this set of pieces that make up the DDD.

In Domain / Subdomains are the problems we want to solve (remember that to solve them we create Domain Models).

And this is where the role of Bounded Contexts comes in: While the Subdomains delimit the Domain, the Bounded Contexts delimit the Domain Models.

💡 Putting it another way: To model a Subdomain, to solve a problem through our software, we must create one or more models of that Subdomain. And to organize these models, according to their Ubiquitous Language, we use Bounded Contexts.

Therefore, the Subdomains are in the problem field and the Bounded Contexts are in the solution field.

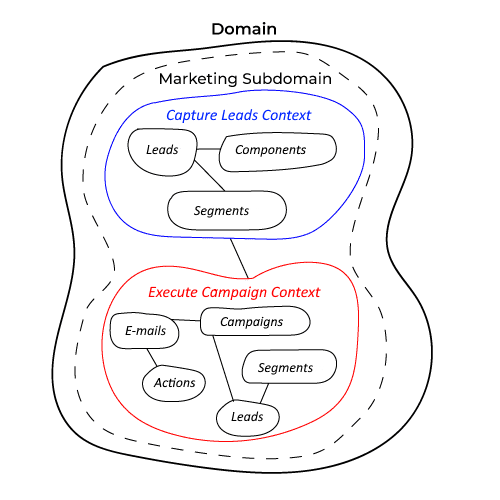

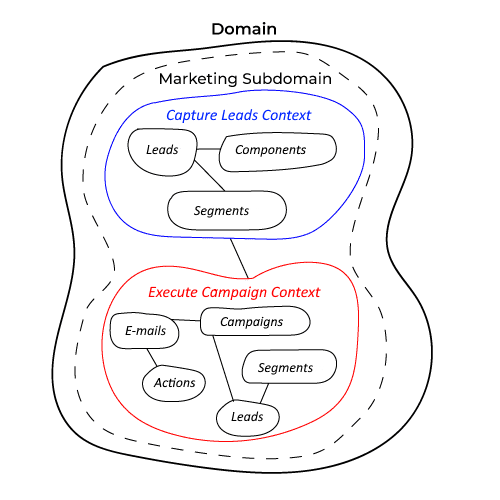

If necessary, we can have more than one Bounded Context for a Subdomain (which is what happens in our Marketing Subdomain):

And according to Vernon, “…it is a desirable goal to align Subdomains one-to-one with Bounded Contexts.”

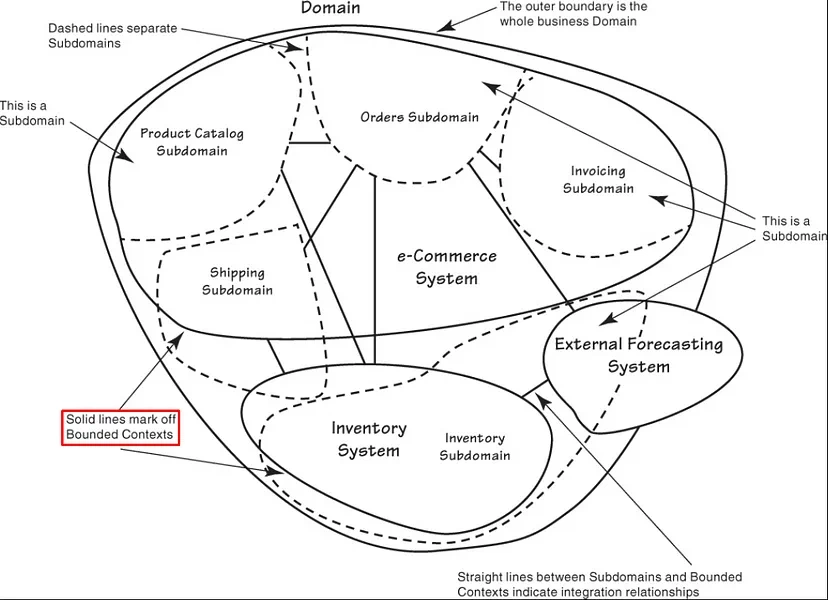

Now let’s look at the domain model of an online retailer, which Vernon uses to demonstrate what happens when DDD is not applied correctly, resulting in too few Bounded Contexts responsible for many business functions:

In the figure above we have two Bounded Contexts: e-Commerce and Inventory. Note that the e-Commerce Bounded Context contains Product Catalog, Orders, Invoicing, and Shipping Subdomains.

These Subdomains are interacting with each other, but there is no clear division between them — they are all merged into this giant Bounded Context called e-Commerce.

On the other hand, the Bounded Context Inventory contains only one Subdomain, which is a desirable goal.

Note: External Forecasting is an external system that is outside the domain model.

That’s why Ubiquitous Language is the most important part of DDD. Because if you don’t understand it right at the beginning of the modeling, you will model it wrong, because you won’t know what they are, nor what your Bounded Contexts contemplate.

Returning to our marketing automation domain

After analyzing the problem in detail together with the domain expert, I realized that our model should be divided into two Bounded Contexts: Capture Leads Context and Execute Campaign Context:

Note: As we saw earlier, in an organization’s domain there are several subdomains. In this image, I’m only representing the marketing subdomain (specifically, marketing automation), as that’s what we’re working with right now. Remember: “…we think of only one area of the business at a time”.

The outermost circle represents the complete Domain. Within it we have the marketing Subdomain, which has the Bounded Contexts: Capture Leads Context and Execute Campaign Context. These, in turn, contain the domain models.

💡 Realize the role of Bounded Contexts, creating a conceptual boundary that delimits the context of the Ubiquitous Language (I talked a lot about the ubiquitous language here, if you haven’t read it, check it out now).

Note that there are different concepts between them (such as Actions and Components), but there are also shared concepts (such as Leads). However, although the two Bounded Contexts share the concept of Leads, they have different data and behaviors.

The Leads aggregate is duplicated between Bounded Contexts because it has a different meaning in each of them. It is perfectly normal for us to do this when we encounter concepts that are shared but have different meanings (properties and methods).

A very common mistake would be to do the opposite. That is, not splitting Leads, keeping all properties and methods in the same class, despite them having no relation.

We often find this type of class that, disregarding the Principle of Single Responsibility, aims to contemplate all the problems of the world, and becomes impossible to maintain (code smell: God Class).

Many times this type of class ends up being moved to the Shared Kernel (we’ll talk about it later), in an attempt to make explicit the intention of using it typically among other Bounded Contexts. But when you open classes like this, by the number of lines and the lack of a well-defined public interface, it’s clear that it should have been split, because it’s overloaded with responsibility.

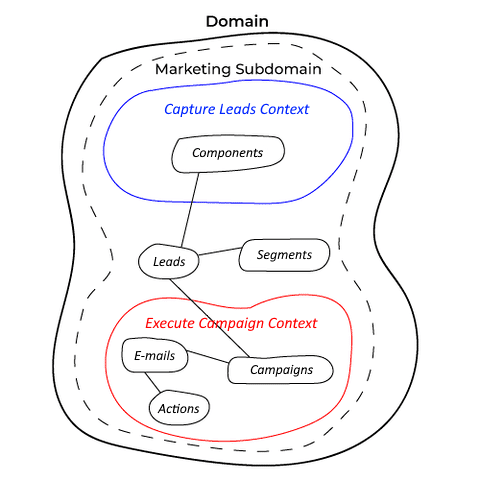

The image below is a representation of this problem:

Note that in this version, Leads have been moved to the Shared Kernel, with the intention of being reused between the Bounded Contexts Capture Leads Context and Execute Campaign Context. However, as Leads has a different language in each of these contexts, we ended up creating a Lead class with too many responsibilities and that does not reflect the language of the Subdomain in which it is inserted.

That is, when we are using Leads in the Execute Campaign Context, there are useless methods and properties.

Thus, it ends up polluting the design, as it forces us to create a public interface that encompasses everything.

See below the Lead class, as it was created in the previous article. It is far from being finished, but it already serves well to exemplify Capturing Leads Context:

On the other hand, in Execute Campaign Context we only need the Email, Name, and Segments of the Lead. Also, in this context, we cannot update the Lead or add new Segments to it:

Vernon refers to this problem as the Big Ball of Mud. Which is a good name to describe the result you get from this type of all-in-one modeling!

Conclusion

You understood that the Domain Model is not a single model, and you understood the importance of organizing our Domain in Subdomains and Bounded Contexts.

I believe that the difference between Domain, Subdomains, and Bounded Contexts becomes clear, and what each one of them is for.

Within the Subdomains, you understand that the most important is the Core Domain.

And above all, I hope you’ve realized the crucial importance of investing time in discovering and refining the Ubiquitous Language, given the fundamental role it plays in modeling.

And make no mistake: Ubiquitous Language seems simple, but in the complex applications we have to deal with in our day-to-day, added to the fact that we have to interact with people from different areas, who use different terms to refer to the same things … it’s a lot of work.

If you have any questions, feel free to ask using the comments section below.

References

- Evans, Eric. Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software. 2004.

- Vernon, Vaughn. Implementing Domain-Driven Design. 2013.